Forty years ago, the Fed pushed the economy into a recession to stop inflation. Here’s how it played out.

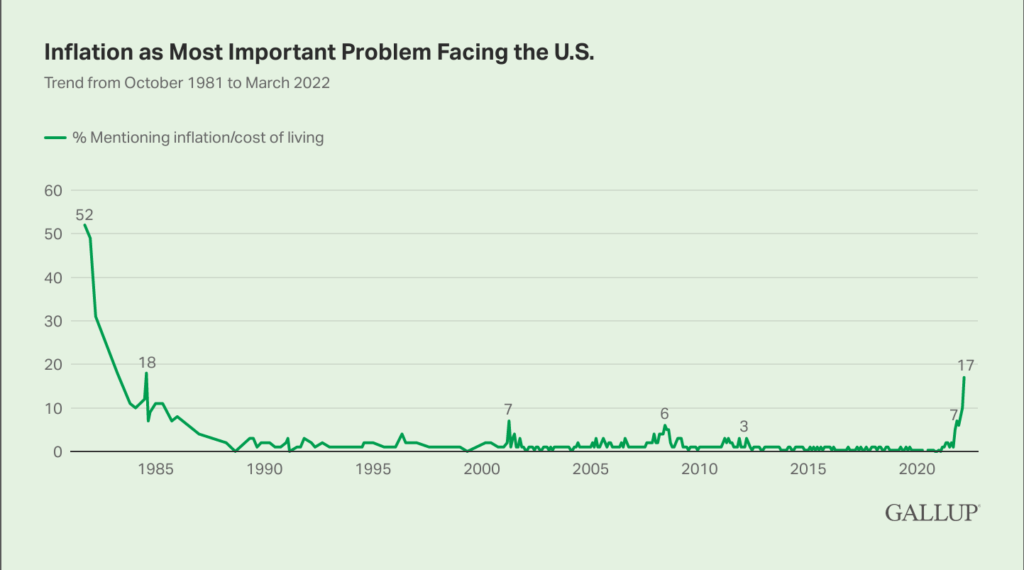

For decades, the polling company Gallup has been asking Americans to list the most important problem in their country. Many of the answers are vague: 19 percent of Americans in May told Gallup that “the government” or “poor leadership” is the most important problem facing the US. Others reflect recent news (5 percent named abortion, up from 1 percent in April), or evergreen topics of controversy (8 percent named immigration).

But the biggest economic issue listed these days, by far, is inflation: 18 percent of Americans listed it as the country’s biggest problem. On Wednesday morning, the latest Consumer Price Index release showed prices up an astonishing 9.1 percent, “the largest 12-month increase since the period ending November 1981.” Even excluding food and gasoline prices, inflation was at 5.9 percent per the CPI, markedly higher than recent years.

As the chart below (which doesn’t include the most recent survey) shows, this is a pretty radical change from recent history. From 1990 to 2020, a tiny share of Americans, always under 10 percent and usually much lower than that, listed inflation as the country’s biggest problem. But the level of concern is still far, far lower than it was in 1981 when the data set starts. That year, a majority of Americans listed inflation as the country’s biggest problem.

In 1981, the US was in the midst of a second brutal stint of double-digit inflation in less than a decade. Gas prices were through the roof; mortgage rates were sky-high, keeping many middle-class people from being able to buy homes. The job market was weak, too, with unemployment above 7 percent. The nation was in full crisis.

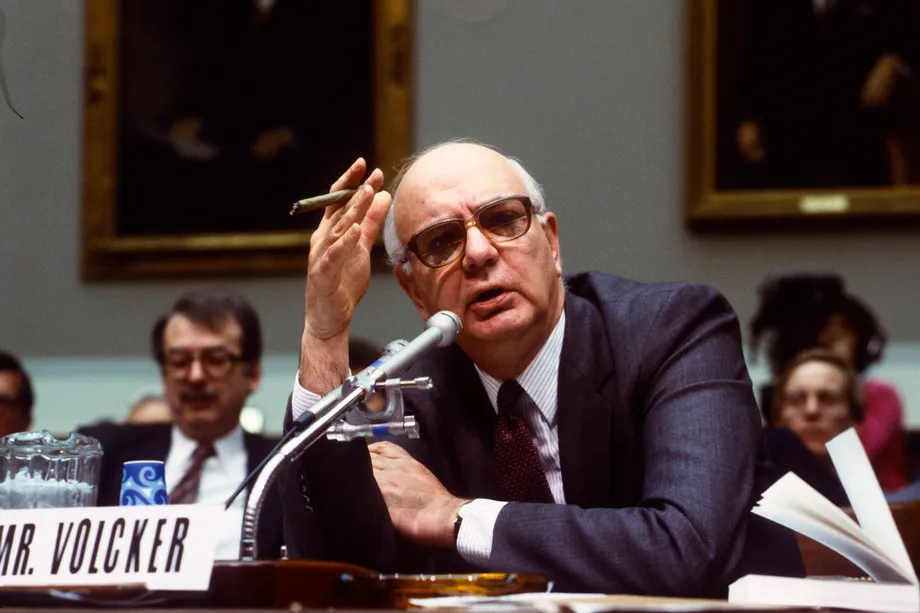

The crisis would end, and most economists give credit for ending it to Paul Volcker, the chair of the Federal Reserve. Volcker got inflation under control through the economic equivalent of chemotherapy: He engineered two massive, but brief, recessions, to slash spending and force inflation down. By the end of the 1980s, inflation was ebbing and the economy was booming.

The 2022 inflation is not as bad as the inflation of 1978-1982 — but it’s the worst inflation the US has experienced in decades. The Federal Reserve is, accordingly, raising interest rates aggressively, as Volcker did. It’s not trying to engineer a recession, but its actions could cause one as an unintended consequence. And if inflation continues to be a major problem, demands for an even more aggressive Volcker-style response will grow.

A rerun of the Volcker shock or something like it is a real possibility, if not a likelihood. Which makes understanding what the first one entailed critical.

How inflation whipped 1970s America

Using the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation — personal consumption expenditures, or PCE, as opposed to the consumer price index, which tends to get much of the attention in news coverage — we can see that prices began to rise, year over year, more rapidly starting around the mid-1960s.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22719955/fredgraph.png)

They fluctuated a bit after a brief recession in 1970, but then surged to great heights, first in 1974-75 and then at the end of the 1970s. After Volcker’s appointment in 1979, inflation peaked and then plummeted rapidly. It has never exceeded 4 percent on an annual basis again.

So what led to the 1960s/’70s inflation, and what did Volcker do to fight back?

Before 1965, inflation was stable for years, hovering around or below 2 percent. But around that time, President Lyndon Johnson and his allies in Congress began implementing big increases in spending, as part of both the war on poverty and the escalating war in Vietnam.

While some of that spending (notably Medicare) was funded by new taxes, much of it wasn’t. That meant higher deficits — and the increased spending, at a time when the economy was near full employment, translated into higher prices. The Johnson administration had no intention of restraining spending; the Vietnam War and his anti-poverty agenda were the president’s top priorities, and he wasn’t going to back down on either. So inflation gradually ticked higher and higher.

Things got worse under Richard Nixon. The Vietnam War was still going on and expensive as ever, but also in 1971, Nixon decided to end the system of “gold convertibility” for dollars.

Prior to that year, under the Bretton Woods system devised in 1944 to stabilize global exchange rates, most Western nations pegged their currency to the dollar, which in turn could be converted to gold at a rate of $35 per ounce.

But this system wound up overvaluing the dollar relative to other currencies. Moreover, there were more dollars floating around than the US had gold to back them. In part due to US inflation reducing the value of the dollar, other countries were beginning to demand conversions of dollars to gold at a level the US couldn’t handle, and some like West Germany were abandoning the system altogether. Under advice from, among others, his Undersecretary of the Treasury Paul Volcker, Nixon blew up the whole system.

He paired this announcement with wage and price controls, meant both to combat inflation sparked by his decision and to fight the inflationary pressures that had already been building before that. Those controls would hold back inflation for a little while — but unwinding those controls later would contribute to much worse inflation.

In 1973, things reached crisis proportions with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ (OPEC) oil embargo on the West, announced as punishment for US and other nations’ support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The price of gas nearly quadrupled between October 1973 and January 1974, contributing to the first of two extreme surges in inflation that decade, and to a relatively long recession ending in 1975.

After that crisis, inflation settled closer to 6-7 percent a year for a bit — not great, but not the double-digit crisis level reached in the depths of the embargo. But inflation soon ramped up again, partially due to surging energy and food prices.

That’s the situation Volcker faced.

The Volcker shock, explained

Before Volcker took office as Fed chair on August 6, 1979, the Fed had tried small increases in interest rates in hopes of taming prices, to little avail. Volcker, as vice chair, was among the hawks on the Federal Open Market Committee pushing for major action. When his chair, William Miller, was appointed treasury secretary by Jimmy Carter as part of a Cabinet shake-up, Carter named Volcker as Miller’s successor.

After a couple of modest increases in the first month of his tenure, he called a surprise meeting on October 6, 1979, and set the Fed on a new, dramatically tighter course of monetary policy. The Fed would allow a much wider band on interest rates, effectively allowing them to go higher than before, and announced it would recalibrate policy regularly in response to changes in the money supply. If the money supply was growing too quickly, the Fed would crack down harder.

That month, the Fed’s interest rate was set at 13.7 percent; by April, it had spiked a full 4 points to 17.6 percent. It would near 20 percent at times in 1981. Higher interest rates generally reduce inflation by reducing spending, which in turn slows the economy and can lead to mass unemployment. When the Fed raises interest rates, rates on everything from credit card debt to mortgages to business loans go up. When it’s more expensive to take out a business loan, businesses contract and hire less; when mortgages are pricier, people buy fewer homes; when credit card rates are higher, people spend and charge less. The result is less spending, and thus less inflation, but also slower growth.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23762234/AP809480244505.jpg)

The approach took two tries to get its intended effect. Volcker’s tightening slowed economic activity enough that by January 1980, the US was in recession. But Fed interest rates actually began falling sharply after April, which limited the effectiveness of the Fed’s anti-inflation efforts. The Fed tightened again after that and sparked another recession in July 1981. This one was far worse than the first; while unemployment peaked at 7.8 percent during the 1980 recession, it would peak at 10.8 percent in December 1982 in the middle of the 16-month second Volcker recession. That’s a higher level than at the peak of the Great Recession in 2009. Over the course of the 1980s, this policy regime would become known as the “Volcker shock.”

When Volcker left office in August 1987, inflation was down to 3.4 percent from its peak of 9.8 percent in 1981, after the first Volcker recession failed to drive prices down. Persistent low inflation has been the norm ever since; the US has never had inflation above 5 percent since September 1983 — until 2022.

Evaluating Volcker’s record

To his admirers, Volcker was the most successful Fed chair in history, a bold policymaker who beat back the inflation problem even when his actions were greatly unpopular.

One of the people who denounced Volcker’s moves was then-Senate Majority Leader Robert Byrd, who declared after Volcker announced his new effort in October 1979, “Attempting to control inflation or protect the dollar by throwing legions of people out of work and shutting down shifts in our factories and mines is a hopeless policy.” Building contractors and carpenters mailed Volcker’s office two-by-fours that they weren’t able to use to build homes, as the mortgage market had dried up. Farmers protested by blockading the Fed headquarters with tractors.

Ben Bernanke, who served as Fed chair from 2006 to 2014, kept one of those two-by-fours in his office, telling the New York Times that Volcker “came to represent independence. He personified the idea of doing something politically unpopular but economically necessary.”

But the program came at a huge human cost that has led critics to ask whether Volcker could have broken the back of inflation in a more humane way, without triggering the highest levels of unemployment since the Great Depression. Historian Tim Barker, in a review of Volcker’s memoirs for n+1, notes that liberal economists of the time like Nobel Prize winners Kenneth Arrow, Paul Samuelson, and James Tobin rejected the idea of an induced recession as unnecessarily harsh.

Barker also blames the “Volcker shock” for setting off a wave of financialization in the US; high interest rates made it hard for brick-and-mortar businesses to borrow for productive investment, and drew foreign money (seeking higher returns) into US banks offering high rates.

The Volcker shock of the early 1980s also set off a debt crisis in Latin America. Many Latin American governments had borrowed from US banks, which charged far higher interest rates after Volcker’s hikes. Debt ballooned, and in 1982 Mexico defaulted on its debts, with others to follow.

The International Monetary Fund stepped in, partially at the urging of Volcker and the Fed, as a lender of last resort, bailing out Latin American governments in exchange for promises to lower deficit spending and adopt structural economics reform. Many governments responded by cutting health and other social services, with critics arguing they worsened the economic plight of recipients and perhaps even cost lives by weakening health systems.

What would a Volcker shock today look like?

Today, the Volcker experience feels more relevant than ever. While inflation, per the Fed’s preferred core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) metric, is still around 5 percent, well below its peaks in the 1970s and early ’80s, it’s nonetheless higher than it’s been in a long, long time.

And the public is furious about it. Consumer sentiment is near where it was in 2008 and 2009, a much, much worse period in terms of economic output and unemployment. Inflation comes up again and again in surveys asking Americans about the biggest problems they face.

A response modeled on Volcker’s would seem to require the Fed raising rates so aggressively as to engineer a recession. That is not the Fed’s current policy posture. In June, it issued its biggest interest rate hike in 28 years. But in his press conference announcing the move, Fed Chair Jay Powell clarified that the board was “not trying to induce a recession now. Let’s be clear about that. … Clearly, it’s our goal to bring about 2 percent inflation while keeping the labor market strong.”

But Powell’s hawkish critics argue that Volcker-style economic pain may be necessary. Larry Summers, the former treasury secretary who came close to being nominated as Fed chair in 2013, has stated, “We need five years of unemployment above 5 percent to contain inflation — in other words, we need two years of 7.5 percent unemployment or five years of 6 percent unemployment or one year of 10 percent unemployment.”

I’m not as convinced as Summers that that amount of pain is necessary. One of the leading reasons for the 2021-22 inflation was that there was too much money floating around quite apart from the labor market, due to factors like government stimulus checks and aid to state governments. And we have rather limited evidence that the current inflation is being driven by rising wages; if it were, that would bolster the case that unemployment needs to rise to keep wages down to constrain overall inflation. But wage growth is actually slowing, which isn’t what you’d expect to see if that story were true.

Ultimately, though, it doesn’t matter what I think. If the White House and Fed don’t succeed in getting inflation under control through their current policy course, discontent will only build and demands will grow for extreme action to solve the problem. Where inflation is concerned, “extreme actions” means something like the Volcker shock, and the Volcker shock means a major recession or two.

That isn’t the likely future of the US right now. But given today’s news, a Volcker-style response has become a little less unthinkable.