The “We Will Adopt Your Baby” signs ring so hollow. Here’s what’s missing.

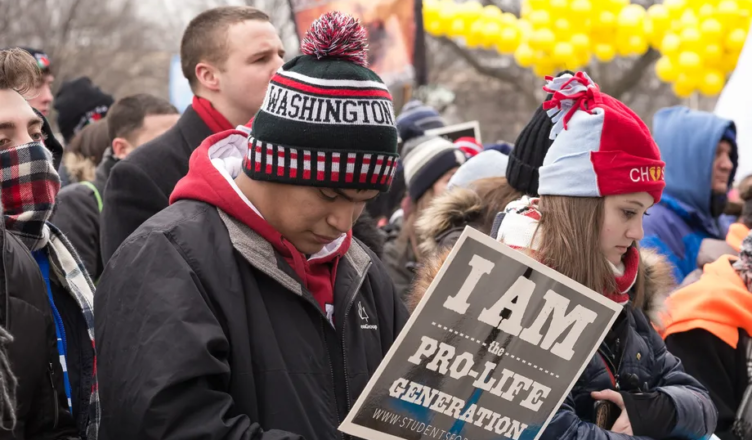

In the immediate wake of the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, social media filled with images and memes playing off a viral tweet: A clean-cut couple beams at the camera while standing outside the Supreme Court building and holding a sign reading “We will adopt your baby.” (Slate has the full story on the couple featured in that photo.)

In a post-Roe world, there is already a renewed focus on adoption as a supposed solution for unwanted pregnancies. Indeed, in the arguments before the Supreme Court last year, Justice Amy Coney Barrett suggested that adoption is a foolproof substitution for abortion. Yet the rhetoric around adoption too rarely takes into consideration the person having the baby who will be adopted.

Kathryn Joyce, an investigative reporter at Salon, has been covering adoption in America for over a decade. Her book The Child Catchers is one of the best ever written about the messy intersections of capitalism, Christianity, and adoption, digging deep into the ways the adoption industry wrings every dollar it can out of an incredibly fragile period in the lives of everyone it touches. (Disclosure: I am adopted.)

Joyce and I talked recently about adoption rhetoric at a time when American reproductive rights have been gutted. That rhetoric touches on so many other aspects of American life, most notably race and class.

“For decades now, there’s been a pro-choice rejoinder to anti-abortion activists: What are you going to do with all these extra kids you want to see born? Are you prepared to adopt all these kids?” Joyce said. “And the answer is: kind of? A lot of people will say, ‘That’s exactly what we want.’”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Photos of couples holding signs saying “We will adopt your baby” have been propagating on Twitter in the past few weeks. As somebody who’s covered this world extensively, how do images like that intersect with your work?

It feels like conversations about adoption that for a very long time were happening in the margins of discussion about reproductive rights are very much more a mainstream discussion. What’s interesting is there have been a few other moments where there has been a similar, if time-bound, recognition of this issue.

In my book, I wrote about what happened in Haiti after the devastating earthquake in 2010. There was this immense rush to not just expedite adoptions that were in process but to open up expedited adoption procedures to any child who was in institutional care in the country, even though welfare experts and even some of the more responsible adoption agencies were saying, “When the country is in complete disarray is not the time to start rushing things.” As part of that, Laura Silsby, a Baptist missionary from Idaho, wrote this extremely blunt and kind of ghoulish plan that she was going to gather [Haitian] children off the street. Ultimately, they were going to be offered for international adoption. The boldness and bleakness of that grabbed people’s attention.

Also, in 2018, when the family separation crisis at the border began to get a lot of notice, there were people who suddenly paid a lot of attention to the fact that one of the largest adoption agencies in the country, Bethany Christian Services, had been contracted by the government to offer a form of foster care for these children. People started asking: What are they going to do with these children that they’re taking away from their parents? Are they going to be offering these children for adoption?

In the aftermath of the Supreme Court overturning Roe, there’s this similarly blunt thing that happened. Two Supreme Court justices — Samuel Alito in his opinion and Amy Coney Barrett in her arguments last winter — made the argument that abortion is not needed because we’ve got adoption. Right-wing politicians have said that adoption is the answer to unplanned pregnancies. And then you have people showing up with celebratory signs and big smiles that say “We will adopt your baby.” That makes it too hard to ignore for a lot of people who weren’t really well-versed in those dynamics.

My favorite sign yesterday. pic.twitter.com/6UsmNy8Q9r

— Noelle Fitchett (@NoelleFitchett) June 25, 2022

Your book primarily (but not exclusively) deals with international adoption, especially evangelical Christian families adopting children, sometimes lots of them, from overseas. How does domestic adoption fit into that picture?

The movement’s rhetoric as a whole is this idea that by adopting, you’re doing something more than just building a family. You are also solving the problem of abortion, because in their mind, you are providing the answer to unplanned pregnancy. Adoption is seen as a seamless solution.

Poverty is the common denominator here. One family is being broken apart for reasons that ultimately boil down to poverty in various complicated ways. Usually, much wealthier families are being created out of a piece of that first family.

When I was doing my reporting for the book, I spoke to the director of an adoption agency in the Pacific Northwest that prided itself on being very open and trying to avoid a lot of the ethical problems that have plagued other adoption agencies. She told me that if you look at all different forms of adoption, the one thing they have in common is the birth mother is invisible. You’re erasing not just the birth mother but the entire family of origin. They’re sometimes seen as the source of a product, as crass as that sounds. It’s how a lot of adoptees have ended up feeling — like a product or a supply.

And these ideas make those families of origin invisible by making them part of a broad caricature. If it’s domestic adoption, it’s got to be some messed-up family or substance-addicted family or abusive family. Or careless, feckless young parents who weren’t responsible. On the flipside, they’re made into these angels who have given the ultimate sacrifice. But they’re never looked at as individual people who, with different resources and support, might have made a different choice.

Internationally, you see a similar thing. The families of origin had been treated for a long time as a terrible situation from which children were rescued, or they were written about in some kind of third-world tragedy terms.

How do you think this intersects with race?

Sometimes in the rhetoric around international adoptions, there’s what a lot of people would characterize as “white saviorism”: These children were thrown away, and the adoptive parents or the church has come along to redeem them. A lot of times, those ideas will involve some fairly severe denigration of the country, the culture, or the family that the children came from.

If you look at the earthquake in Haiti in 2010, there was an extreme version of that rhetoric, with people talking about Haiti as this doomed or even satanic country. There was a sense of saving these children from growing up in that country. And the leaders of Haiti pointed out at the time, “What are you saying about our country if you say the only chance our children have is to be taken out of it?”

In the last 20 years, transracial adoptees in particular have talked about their experiences with this. Generational waves of adoptees of a certain age come from a particular country because that country was a hot spot adoption center at the time. So there is this older wave of Korean American adoptees [from the 1980s] who were pioneers in a lot of this research and advocacy. They talk about having many times grown up in an area where they were the only person of color. And Black or Latinx adoptees, whether they were adopted domestically or internationally, say similar things.

Even adoptees who had really happy situations and were close with their adoptive family will say that something that was missing was the understanding of what it would be like to grow up a person of color in a largely white community.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23786862/GettyImages_675653308a.jpg)

The natural question is: Why aren’t the folks who were holding those signs not just adopting kids in foster care? Obviously, it’s not that simple, but I’m still asking myself that question.

There are different dynamics at play. A lot of times people who want to adopt do want to adopt infants or young children. There is a perception that children who have been in the foster care system are damaged in some way. Sometimes, there are weird racial dynamics. There have been adoptive parents who have distinguished, racially, between Black kids in the foster care system in the US and Black kids who were available for adoption from countries in Africa. They would say, “My kid’s not Black. They’re Ethiopian.”

But the foster care system also has a ton of problems. The majority of kids who end up in the child welfare system in most places in this country are overwhelmingly there not because of child abuse but because of things that fall under the category of neglect. To people who haven’t paid that much attention to it, it’s easy to conclude that kids who are neglected aren’t being fed and aren’t safe and need to be taken away. But that’s often not what neglect ends up meaning.

Most of the time, it boils down to things that, again, are about poverty. There are huge racial disparities there, but also really significant classist elements. Poor white families also often end up on the wrong side of that scrutiny. The neglect that ends up separating so many kids from their families in poorer communities in this country is so subjective.

Kids end up in this system because they wore dirty clothes to school, or because a school nurse found lice, or because their parents were trying to get substance-abuse treatment. Most of these things just boil down, ultimately, to them being poor. If we were a country that provided better resources to deal with these things, it wouldn’t result in a system that starts its own catastrophic chain of events, both for families but also for the system as a whole when it starts taking in way more children than it can responsibly care for.

Obviously, lots of people are adopting because they can’t have children for whatever reason. But what do you see as overriding motivations about adoption within these religious communities, even in families that are only adopting two or three kids?

Everybody’s in an individual situation, and most people, the primary motivation is to either build or expand their family. That remains true.

When I was writing about the Christian adoption movement 10 years ago, there was this concerted effort to cast adoption not just as something individuals did for all the reasons that people do things, but to cast it into a religious mission, where they would be doing a number of things simultaneously. They would be solving the “orphan crisis,” which was this argument that there are hundreds of millions of children who are orphaned and in need of adoptive homes around the world. And the other argument was they could solve the abortion question. They could provide the homes that pro-choice advocates were constantly challenging and asking for when they would say things like, “Are you prepared to adopt all these extra kids?”

As the movement really got into full swing in the late 2000s and early 2010s, a lot of religious leaders started writing books making a theological case for adoption as well. A lot of those books would point out what they saw as a parallel between the adoption of children into a family and the way Christians were adopted into God’s family when they accepted Christ. So they would say, if you adopt, you are capturing this divine pattern in your family. Some of the books made an argument that the ultimate purpose of adoption is fulfilling the Great Commission mandate that you are going and converting the nations of the world, that you are evangelizing through adoption.

The physical toll a pregnancy takes on someone’s body is substantial, but as we talk about birth families, I want to think about the mental and psychological effects of going through a pregnancy and giving the child away, even if you are doing so willingly. What do those look like?

The reason I ended up writing about adoption in the first place is I was speaking to a lot of the women who had relinquished their children during the baby scoop era, before [1973’s] Roe v. Wade. Unwed parenthood was so shameful that a lot of white women got sent away to these maternity homes, so they could go through pregnancy and deliver, then pretend nothing happened.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23767696/929339492.jpg)

I was speaking to these women decades later, and they were still so raw from that loss. It had come to define their life. Everyone I spoke to felt at least coerced, like they were not given a real chance to make a decision to parent. They said all kinds of things, like they would have PTSD reactions if they heard children crying, or that some of them never stopped thinking about where their child was and if they were okay.

Some of the mothers I spoke to who had this experience talked about this as a form of ambiguous loss. That’s a term they often use for families of someone who has gone missing. In some ways, that can be harder to deal with than if somebody has died because you are living constantly in this state of uncertainty.

Adoption is always going to exist. It’s always going to be part of how humanity handles children who need homes. But we’re also entering an era when there might be a lot more of it. What are some things we could do as a society to make adoption less traumatic for everybody involved?

It needs to be a truly informed choice, which is something we haven’t seen, outside of certain circumstances. But it’s never been the main experience of people relinquishing children for adoption.

So many people have talked about forms of pressure they encountered. They might have to fill out these questionnaires that make them feel like there’s no way they are prepared or wealthy enough to raise a child, which is a pretty subtle form of coercion. But there’s more overt ways, like outright telling people there’s no way they could be a good parent and if they keep their child, they’re being selfish.

We would need to start asking: Has this person or their family been offered the material resources that they are most likely lacking to be able to keep their family intact? There’s a lot of talk, even among adoption advocates, that adoption should be the last resort after trying to reunite a family, or trying to keep a child within an extended family or within their community — or at least within their country, if it’s international.

In practice, it’s never worked out that way because those options cost the state money. If you’re really going to support families, in the way that a handful of Republican politicians say they are willing to consider doing now that they have outlawed abortion in many states, that is going to cost a huge amount of money. The adoption industry is a private, market-based solution to that problem that generates money for Western businesses and all of the middlemen that get involved.

We haven’t ever really tried a system that’s non-coercive. But I also think you can’t talk about that prospect without the bedrock choice that people need to have: to decide whether to go through with a pregnancy. Most people involved in adoptions, most people who have relinquished custody, will tell you that whether or not to continue a pregnancy is a very different decision than whether to parent that child.